Listen to the article

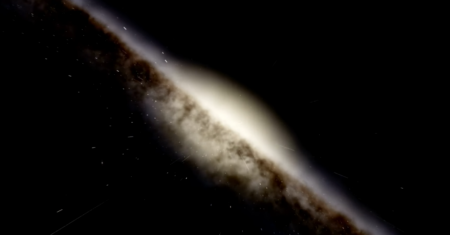

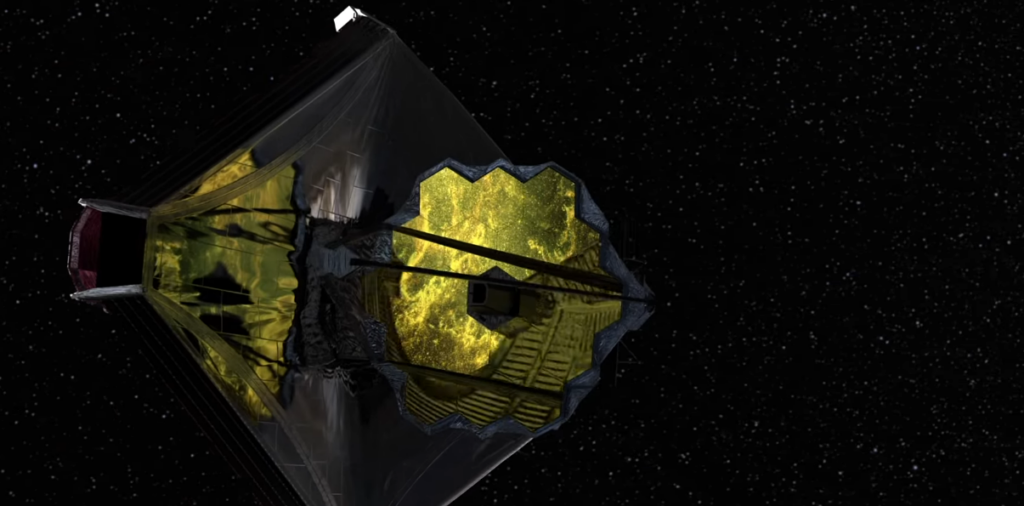

Astronomers had gazed into that piece of space many times. This time, however, the James Webb Space Telescope, equipped with extremely sophisticated optics and increased sensitivity, observed something strangely unexpected. Six blazing-red smudges were concealed in the primordial darkness that dated back more than 13 billion years. They weren’t clouds of gas. Nor were they merely far-off stars. They were galaxies. Completed, frighteningly enormous galaxies.

These were not merely dimly glowing structures. They appeared just 700 million years after the Big Bang, indicating a level of maturity that should have taken billions of years to evolve. They raced over the cosmic history. The weight of one galaxy, ZF-UDS-7329, was over ten times that of the Milky Way. Just that fact shivered observatories around the world.

The distinctive redshift signature—the light stretched to longer wavelengths over vast distances—was detected by scientists using Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera. Not only were these galaxies early, but they were also old, existing closer to the chaotic beginning of the universe than anything we would normally consider normal. It wasn’t merely out of the norm. It was essentially startling.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Telescope | James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) |

| Discovery | At least six massive galaxies formed 500–700 million years post-Big Bang |

| Notable Galaxy | ZF-UDS-7329 (one of the “red monsters”) |

| Challenge | Formed too early and too large for current galaxy evolution models |

| Possible Implications | Forces revision of early-universe cosmology |

| Published In | Nature, NASA Science, Scientific American |

| Observational Tool | Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam), Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) |

| Official Reference | NASA Science – JWST |

It would need remarkably high star formation rates—possibly 100 stars annually, as opposed to the modest speed of one or two in our Milky Way—to produce something that massive, so rapidly. Additionally, they would have had to accomplish this in an atmosphere that was believed to be mostly devoid of metals, dust, or gravitational scaffolding that would have sped up such quick growth. Clearly, the math is flawed.

Theories started to change. These might not have been galaxies. Gravitational lensing frequently produces illusions in deep-space imaging; it’s possible that the light was magnified by an obstructive object. However, that explanation was insufficient this time. The brightness and shape could not be explained by foreground lenses. All that was left was a strangely enduring, softly disturbing object.

Notably, scientists are now faced with a conundrum: if even one of these galaxies is verified, it indicates a basic gap in our knowledge of the early cosmos. Maybe the early universe was far more efficient than we thought—more capable, more motivated, and less forgiving of delay—or maybe our models are lacking.

It’s important to note that opinions among scientists about the implications vary. Some speculate that we might be misinterpreting the evidence and conflating early galaxies with quasars, which are galactic centers driven by supermassive black holes. Others question whether the instruments are absorbing a completely different kind of structure—something that hasn’t been given a name or categorized yet.

I heard a reputable scientist stop during a quiet period in a recent symposium livestream before responding, “These galaxies shouldn’t have had time to form.” I remembered that statement because it was so incredibly obvious, not because it was dramatic.

Webb’s onboard spectrograph, NIRSpec, is responsible for the following stage. By measuring these galaxies’ chemical fingerprints, scientists will be able to examine their composition in greater detail. We could have to reevaluate long-held beliefs if the spectra validate the presence of dust, heavy elements, and dense star populations. Timelines can change. Equations can change over time.

This problem is not only intriguing, but also useful. After all, tension is what science thrives on. Every anomalous data point presents a chance for improvement, reworking, and rethinking. Even though it frequently takes a very long time, that approach is incredibly successful in advancing our knowledge.

These kinds of oddities are catalysts rather than issues in the context of cosmic exploration. They drive difficult discussions about what we know, how we know it, and what we’ve missed while pushing disciplines to the limit of their comfort zones. These six galaxies may be doing just that as they silently glow at the edge of space.

Organizations such as NASA, ESA, and independent observatories in Europe and Asia have been lining up telescope time proposals for several months. It makes sense that there be hurry. You take quick action, even if it means changing your own hypothesis, when six galaxies contradict logic rather than waiting years to look into it.

The way that Webb is exposing the unexpected has a really adaptable quality. It was intended to gaze back in time and see the first stars flicker. Instead, it might be demonstrating that our story’s opening chapters are far more vivid, quick, and dense than anyone had anticipated.

The telescope has evolved beyond a lens by pushing the limits of observational astronomy and known physics. It softly changes narratives without demanding a headline, making it a disruptive engine. For a generation of scientists who were brought up on cosmic stability and are now experiencing something more dynamic, it is especially advantageous.

Scientists have constructed a solid framework for understanding the formation of galaxies through decades of simulations and supercomputer modeling. However, even robust structures require periodic examination. These early galaxies are demonstrating to us where the rules never fully fit in the first place, not breaking the laws.