Listen to the article

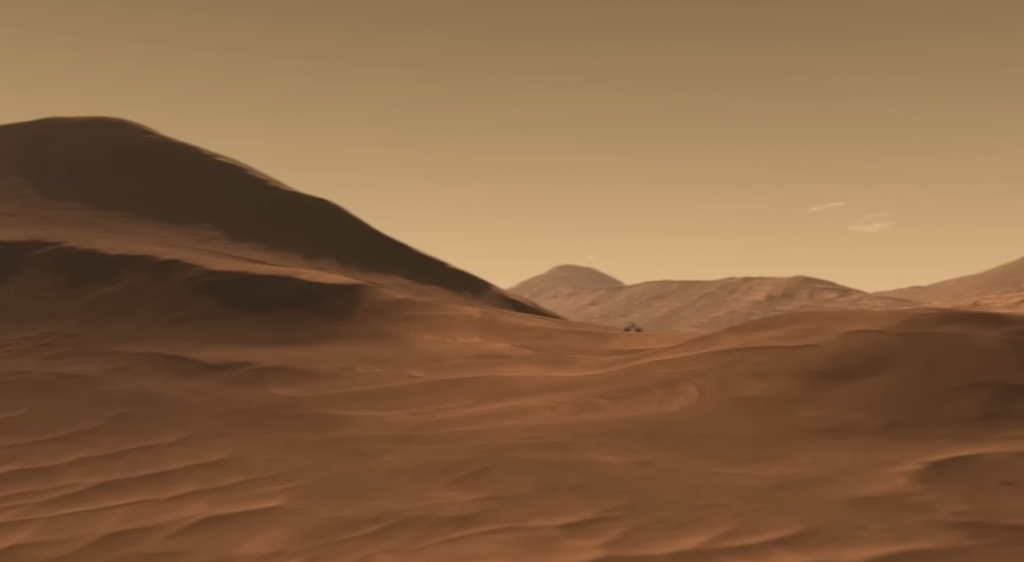

In the last ten years, researchers have started to characterize Mars less as a perpetually frozen desert and more as a planet that went through a tremendously vibrant youth, molded by water that moved patiently and persistently. Once thought to be haphazard rock formations, these are now being understood as the remains of coastlines, sculpted slowly and very clearly by extinct rivers and waves.

Looking at an image of the Martian terrain in a museum years ago, I recalled how closely similar its dry pathways were to riverbeds I had seen during a drought in Arizona, implying absence yet subtly conserving remnants of earlier plenty. As NASA’s findings have significantly improved, transforming hazy conjecture into organized scientific assurance based on multiple observations, that recollection has frequently come back.

Researchers discovered fan-shaped sediment layers in Coprates Chasma, a system of canyons that stretches across Mars with an almost scary magnitude, by examining high-resolution imagery taken by orbiting spacecraft. Only when rivers feed into stable seas that last long enough to alter the terrain do these formations, which are formed by flowing water slowing as it reaches a wider basin, seem especially congruent with river deltas on Earth.

Scientists interpret the horizontal pattern of these geological markers, which were discovered at astonishingly consistent elevations, as an ancient shoreline that has been maintained throughout billions of years of exposure to radiation, wind, and time. Because this consistency implies that Mars did not host water for a short time but rather sustained seas long enough for complex environmental stability to develop, it is especially helpful to researchers.

| Key Fact | Details |

|---|---|

| Discovery | Geological evidence suggests Mars once had a vast ocean covering much of its northern hemisphere |

| Time Period | Approximately 3.7 to 4.3 billion years ago |

| Key Location | Coprates Chasma canyon system, part of Valles Marineris |

| Supporting Mission | NASA Perseverance rover found potential biosignatures in ancient riverbed rocks |

| Ocean Size | Possibly larger than Earth’s Arctic Ocean |

| Habitability Implication | Long-lasting surface water could have supported microbial life |

| Reference | https://www.nasa.gov/mars |

According to calculations made during previous NASA atmospheric research, Mars formerly had an ocean that was larger than Earth’s Arctic Ocean and stretched across enormous plains, covering a large portion of its northern hemisphere. When estimating the amount of water that Mars lost to space when its atmosphere thinned considerably, this estimate—which was constructed by monitoring hydrogen isotope ratios—proved to be incredibly accurate.

Water was able to evaporate or freeze permanently as a result of the gradual and harsh loss caused by solar radiation removing air shielding and lowering pressure. Geological data that today acts as a scientific archive was left behind when Mars changed over millions of years from a wet and perhaps livable planet to a frigid and silent place.

The discovery is especially groundbreaking in the field of astrobiology since oceans offer microbial colonies incredibly dependable mineral conditions, energy gradients, and chemical stability. Similar conditions on Earth made it possible for simple organisms to arise incredibly early. Long before complex life emerged, these organisms were able to sustain themselves and produce energy through chemical reactions.

This notion was reinforced by NASA’s Perseverance rover, which used extremely effective instruments inside Jezero Crater to identify rock samples that included phosphorus, iron minerals, and organic carbon. Even while there are still scientifically viable non-biological explanations, the discovery is especially significant since these components, when coupled in particular configurations, can support microbial metabolism.

By looking at the rover’s mineral maps, researchers found what are known as reaction fronts—patterns where water and rock formerly interacted chemically, possibly generating microbes’ energy sources. Since these structures can be created chemically or biologically, they are extremely versatile markers. As such, each sample needs to be carefully and patiently examined before any conclusions are made.

After reading the Perseverance analysis late one night, I became surprisingly optimistic when I realized that each mineral pattern represented a preserved moment in planetary history that needed to be understood, rather than just chemistry.

NASA has taken an incredibly successful approach, concentrating on areas where life would have had the best chance to arise and persist: river deltas, sedimentary basins, and putative shorelines. These regions are especially useful for maintaining organic traces that would otherwise deteriorate under severe surface conditions since they are formed by water and shielded by sediment.

Mars has started to unveil a connected hydrological network through ongoing rover exploration and orbital mapping, demonstrating that rivers formerly consistently fed lakes and seas across great distances. This network would have supported remarkably favorable environmental conditions for life development by allowing chemical nutrients to circulate as part of a highly efficient planetary cycle.

Scientific confidence that livable habitats can exist beyond Earth has significantly increased throughout time as a result of the discovery that Mars has maintained stable water systems for millions of years. This change has inspired scientists to explore Mars more urgently, approaching each finding as a piece of a larger story rather than as a stand-alone curiosity.

Returning Martian rock samples to Earth is anticipated to be a particularly creative task for future missions, enabling researchers to employ laboratory instruments that are far quicker and more accurate than rover-based technologies. These samples might validate chemical reactions that strongly suggest ancient living activity or provide tiny fossil evidence.

It is anticipated that developments in robotics, drilling technology, and planetary protection procedures would make Mars exploration incredibly dependable in the upcoming years, enabling the investigation of deeper subsurface strata. Because these layers are protected from radiation and kept in cooler temperatures, they might include organic material that has withstood the test of time.