Listen to the article

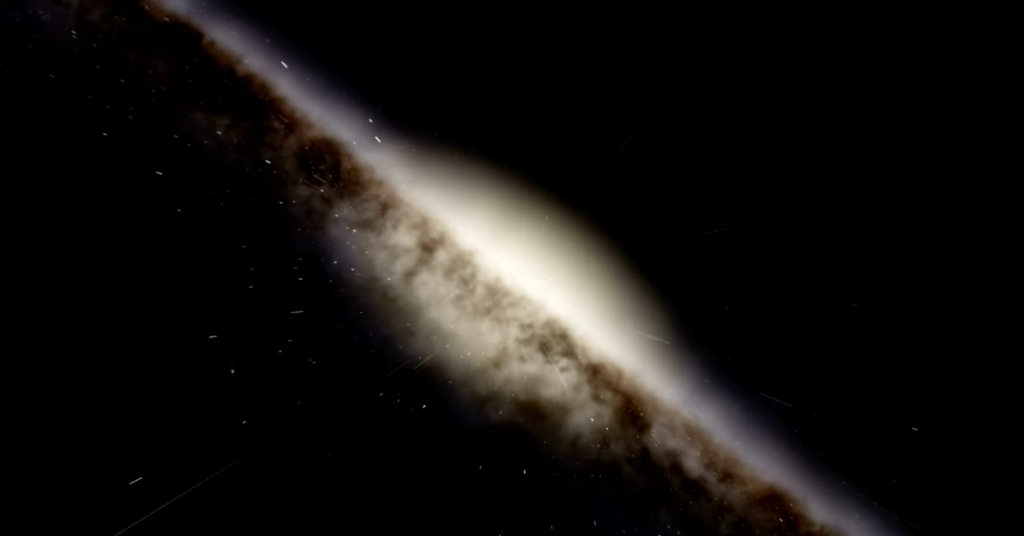

A brief but dazzlingly bright occurrence illuminated the far sky in July 2025. It was something far more subdued and terrible than a supernova or an extraterrestrial communication. A star that had wandered too near had been torn apart by a black hole, which might be wandering between galaxies. The devastation was seen in motion and captured in ultraviolet light for the first time.

Compared to typical gamma-ray bursts, the signal, now known as GRB 250702B, burned for a longer period of time. This one lasted for hours, leaving an afterglow that pulsed with eerie clarity, rather than vanishing in a matter of seconds. Scientists were taken aback. It was as dazzling as entire galaxies and seemed to appear out of thin air, a full-scale cosmic ambush.

Scientists located the source in a previously uninhabited area of the sky by comparing photos from several telescopes. This was not the busy center of a galaxy, which is where giant black holes usually live. Rather, it was asymmetrical—possibly an indication of a dislocated or “wandering” black hole, silently moving through the night like a ghost under the influence of gravity.

According to reports, the image was very clear. As the star was drawn into an impossible-to-thin stream, stretched like spaghetti by tremendous tidal forces, astronomers monitored the ultraviolet signature using Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope. It may sound like science fiction, but when a star near a black hole crosses a threshold, this “spaghettification” process occurs with alarming accuracy.

This one did not make it.

| Event Name | GRB 250702B / “Scary Barbie” |

|---|---|

| Type of Event | Tidal Disruption Event (TDE) |

| Observed Phenomenon | A black hole devouring a star |

| Discovery Date | Initial burst recorded on July 2, 2025 |

| Distance from Earth | Approx. 600 million light-years |

| Telescope Involved | Hubble, Webb, Fermi, Swift, NuSTAR, Gemini, VLT, Chandra |

| Black Hole Mass | Estimated 1–10 million times the mass of our Sun |

| Key Visual | UV and X-ray imaging of “spaghettified” star matter |

| Uniqueness | First detailed capture of such event in ultraviolet light |

| Scientific Implication | Rare proof of a black hole consuming a star outside a galactic core |

The matter superheated as it spiraled in, creating an accretion disk that emitted ultraviolet and X-ray radiation. It took 600 million years for the radioactive flare to reach Earth. In other words, we are witnessing the last flaming scream of a star that died before dinosaurs inhabited the earth.

The way telescopes worked together was what made this discovery so groundbreaking. Webb recorded infrared emissions, while Hubble monitored ultraviolet details. High-energy radiation signatures were locked down with the aid of Swift and NuSTAR. Astronomers were able to produce an exceptionally comprehensive image of a star’s dramatic demise because to this collaboration.

When explaining the chronology, one researcher observed that the incident “didn’t match anything we’ve seen before.” That comment stuck with me because it showed how astronomy still has room for amazement, not because it suggested disorder. especially seasoned scientists can be surprised by the cosmos, especially with the abundance of digital archives and modeling tools available.

The aftermath had a really poetic quality. There was no remnant left after the star crashed inward. No neutron star. No detonation. A ring of hot gas spiraling down a gravitational abyss, and a last display of light. The event finished in silence, which is an extreme type of closure that only space can provide, despite all of its drama.

This observation, which was remarkably successful as a scientific finding and a technical milestone, now guides researchers’ hunt for comparable occurrences. Astronomers can increase their chances of spotting another TDE in real time by fine-tuning telescope filters and giving particular wavelengths priority.

By means of strategic collaboration, the group discovered not only a single solution, but also a way to open dozens more. When looking for abrupt flares in the sky, future sensors will prioritize the ultraviolet signature, which turned out to be a critical fingerprint.

I recall reading the final energy estimates with a mixture of amazement and fear. Its host galaxy was outshone by the flare. Over several days, it emitted more light than a trillion suns. Then it vanished.

The thought that this might occur again—possibly more fiercely and closer—lingers. Moments of hunger are revealing black holes, which were previously believed to be silent and unseen. They glow while they eat. Just long enough for us to notice, not forever.

This incident establishes a precedent for medium-sized telescopes that continue to search the sky. Similar events might become more frequent with the correct filters and quicker reaction times. This is especially useful for simulating the role of star death in galactic evolution or the possibility that mid-size black holes are significantly more prevalent than previously thought.

This is not merely theoretical science. Understanding the mechanics of this event gives us the ability to decipher cosmic messages, some of which might eventually originate from even stranger sources. Consumption of a neutron star. A white dwarf that was split in two. Perhaps something really unexpected may happen one day.

GRB 250702B serves as a subtle yet sobering reminder that nature continues to write better scripts than humans in the realm of cosmic study.

The answer to the question of whether black holes are lurking close to us is yes, but you shouldn’t be alarmed. These things follow the laws of gravity, even when they are most hungry. We would notice its impacts well before its teeth if one got close.

Nevertheless, this finding provides some encouragement. It demonstrates that our tools are functioning, our teamwork is fruitful, and our curiosity is being rewarded with insight. By focusing on previously unnoticed locations—those peaceful areas in between galaxies—we can find more tales that shine before disappearing.