Listen to the article

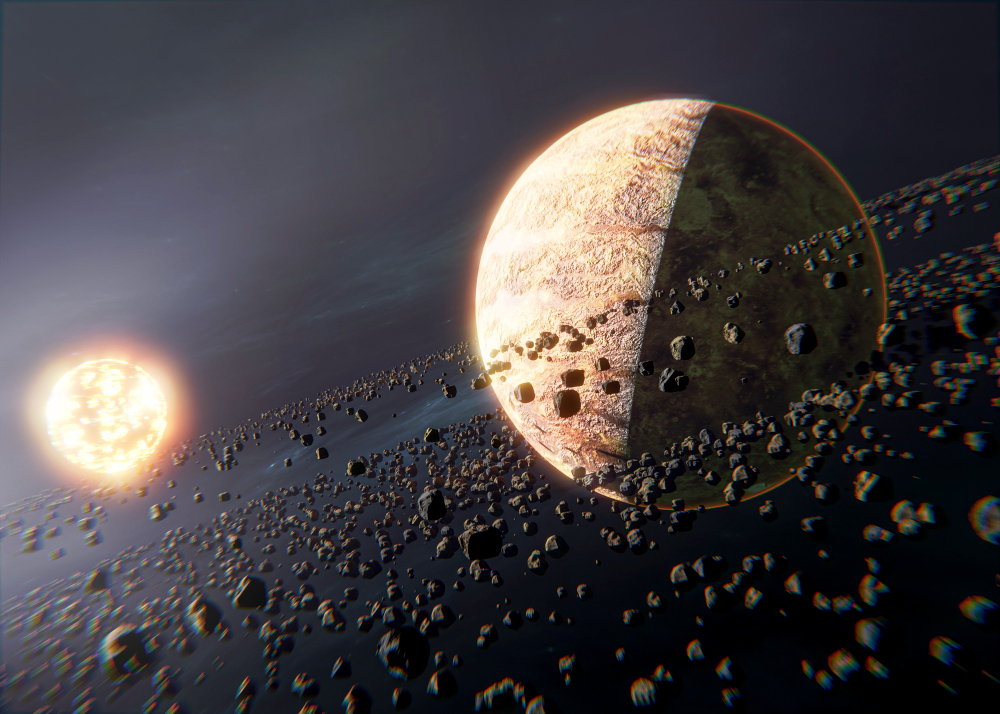

In January 1986, Voyager 2 flew past Uranus and sent back to Earth grainy images of Miranda, marking the last time humanity saw it up close. There was something off about that little gray-white moon, even through the static and blur. Its surface looked like it had been stitched together, with enormous grooves cutting across it at odd angles and cliffs rising like broken teeth. It didn’t appear to be dead. It appeared to have been interrupted.

Scientists believed at the time that Miranda was just what it seemed to be: a frozen relic that was too small and far from the Sun to support any living life. It was only roughly 470 kilometers in diameter, which was too small to retain heat inside. Instead of considering it a location with genuine potential, it seemed safe to file it away as a geological curiosity.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Object Name | Miranda |

| Type | Natural satellite (moon) of Uranus |

| Diameter | ~470 km |

| Discovery | Discovered by Gerard Kuiper in 1948 |

| Key Discovery | Evidence suggests subsurface ocean 100–500 million years ago |

| Possible Ocean Depth | Up to 100 km deep |

| Parent Planet | Uranus |

| First Close Images | NASA Voyager 2 (1986) |

| Scientific Significance | Possible ocean world and candidate for extraterrestrial life |

| Reference | https://www.nasa.gov |

However, decades later, as they sat in quiet offices with old spacecraft data and humming computers, planetary scientists began to ask a different question. What if the scars weren’t merely superficial? But what if they were signs?

Like detectives reconstructing a crime scene, a team comprising researchers from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory started going over the Voyager images again and modeling Miranda’s internal structure. Something unsettling was implied by their simulations. Miranda probably had a huge subterranean ocean between 100 and 500 million years ago, hidden beneath a thin layer of ice that was only 30 kilometers thick.

That ocean might have never completely vanished.

The concept seems illogical. Miranda is almost 2.9 billion kilometers away from the Sun, where sunlight is barely perceptible. If one could stand there, Uranus would loom over the sky like a silent, slanted giant, and the sky would seem perpetually dark. The atmosphere conveys a sense of immobility, permanence, and freezing.

But expectations are complicated by gravity.

According to scientists, Miranda was formerly in orbital resonance, a gravitational rhythm with nearby moons. Its interior would have been flexed by this continuous pulling, creating heat and friction that would have gradually melted the ice into liquid water. Oceans on other far-off moons, such as Europa and Enceladus, which are currently regarded as two of the most promising locations to look for extraterrestrial life, are maintained by similar processes.

Miranda’s diminutive size in relation to those worlds is remarkable. It was not intended to be eligible.

One of the participating scientists, Tom Nordheim, acknowledged that even the research team was taken aback by the discovery. Miranda’s surface appears to have ridges and cracks that correspond to stress patterns produced by a liquid interior pressing against a frozen shell. Those patterns would probably appear different—more consistent, more definitive—if the moon had fully frozen solid.

Rather, they appear incomplete.

Examining those pictures gives the impression that Miranda may still be evolving beneath the surface, gradually becoming quieter but not yet quiet. Even from millions of kilometers away, it’s difficult to avoid feeling the same sense of curiosity that has propelled exploration for centuries as you watch this unfold.

Is the water down there still there?

Scientists aren’t prepared to make that guarantee. According to the models, any ocean that remains would be thinner than it was previously, perhaps trapped in isolated areas. However, the frozen-forever theory is called into question by the lack of some surface fissures, which would have developed if liquid water had completely frozen.

Whether Miranda is dead inside or not is still unknown.

Water alters everything, so that uncertainty is important. Life tends to follow wherever there is liquid water on Earth, sometimes in unexpected places. far below the Antarctic ice. in the vicinity of ocean bottom hydrothermal vents. concealed by the shadows.

Maybe Miranda isn’t all that different.

It is hard to ignore the wider implication. For many years, scientists believed that the outer solar system was mostly inactive and that its smaller moons were irrelevant. However, findings like these are compelled to quietly reconsider. Ocean worlds, dispersed throughout the shadows like sealed laboratories, might be far more prevalent than anyone realized.

And oddly enough, Miranda may be one of them.

The fact that almost all of our knowledge is based on a single flyby from almost 40 years ago is another unsettling fact. Since Voyager 2, no spacecraft has visited Uranus again. When compact discs were still a new technology and Ronald Reagan was president, the data that scientists use today was recorded.

Miranda might have been waiting the entire time.

Although no missions have yet to launch, there are plans to send more to Uranus. If so, it might be equipped with instruments that can measure gravitational anomalies, detect heat signatures, and even sample particles that are ejected from the moon’s surface. These would be minor hints, but sufficient to verify whether liquid water can endure cold temperatures.

Miranda is still in between categories until then.

Not quite alive. Not quite dead.

Simply waiting, circling in silence in the gloom, bearing the hope that something surprising is still in motion beneath its frozen and cracked face.